By Andrew Sheppard

My congregation has been well-trained to inhabit the language of abundance. This is not the case because of any material change in circumstance, but rather because of the diligent teaching of many of our church leaders. It is not a concept that comes naturally, especially to a lot of rural mountain folks, but our ministers and teachers have, through sound and frequent reminders of what the Kingdom of God is like, introduced a somewhat foreign theological concept into our communal lexicon. And for this, we give thanks.

A theology of abundance has the capacity to really shape a lot of other discussions and decisions that might follow. It is not easy work, of course, swimming against the cultural current, but having this shifted framework has been a gift in shaping our congregation’s life together, especially as we determine what’s most important to us. While the concern of financial resources never really goes away, it is impossible to ignore how markedly different it feels to sit on our church’s finance committee, preparing a budget and responding to benevolence requests with equal measures of prudence and faith. In short, a theology of abundance makes way for wisdom to dictate our conversations, not just about money, but about every work of the community.

And yet, though the language we use shapes our collective disposition toward these things, we still live in a world where there is the reality of resource imbalance. We know that this is how the game board is set before we even begin to play, and though our language of abundance allows us to think, speak, and act differently about these things, we are no less immune to the realities of resource imbalances. I would hardly blame a member of my community for turning their nose up at the idea that there is more than enough of what we need in the Kingdom of God. This is jarring. I tend to assume that when we give something the language it requires, our attention is automatically turned toward the thing, and our imaginations are, in turn, shaped in such a way that we get to work on preparing the fields for rain, so to speak. It can feel dishonest, at times, to talk about abundance in a presumptive way. I get the sense that, for many, an abundance in a coming Kingdom is only good news with a big asterisk.

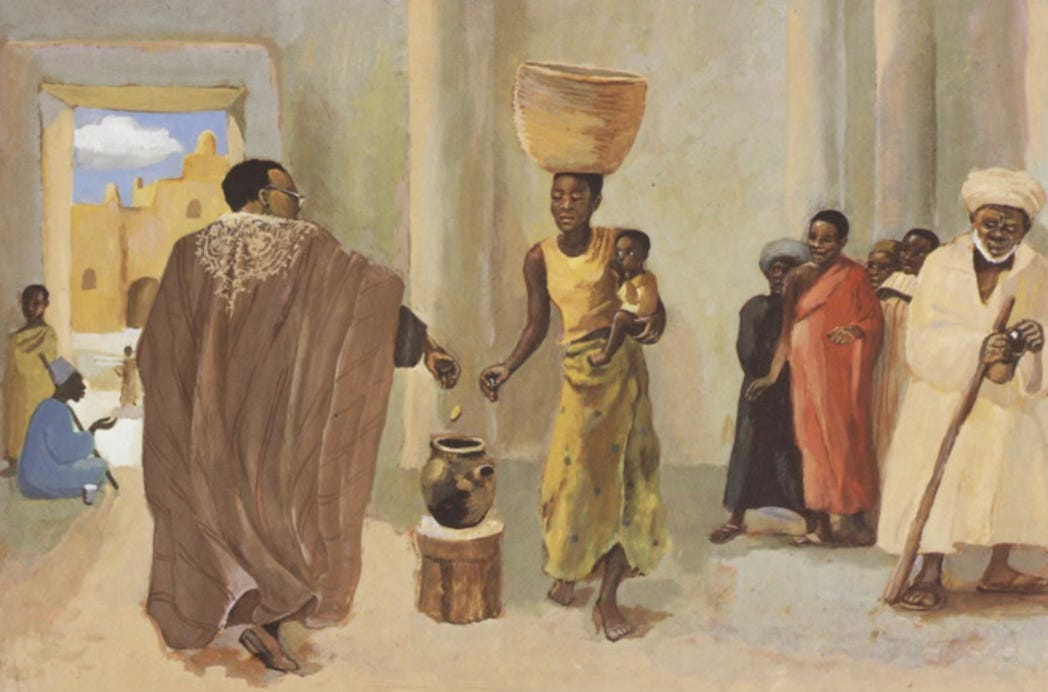

I say all this as I try to put myself next to Jesus as we sit opposite the treasury, keeping an eye on what’s going on. As I sit next to the teacher, it becomes evident to me, both as he speaks and as I watch, that the pieces are all in place. The wealthy, as ever, are drawing attention to themselves. They move freely in the world, unburdened by the usual sorts of things that might wear a person down. They expect a grand welcome wherever they go. As the world is, both then and now, they are marked by abundance. Even Jesus calls it that way. There is no getting around the reality of their prosperity and profusion. But abundance like this is missing something. It might be “real” in some painfully obvious ways, but this abundance is, paradoxically, extremely limited. It is short sighted, both in time and scope. It is the kind of abundance that serves immediate purposes of surface level respect and economic participation. (It should come as no surprise that Jesus identifies these types with the scribes found in their most comfortable ecosystem: the marketplace. It is here where their abundance is legitimized). Abundance in this sense is always inward looking, oriented toward the immediate. This kind of abundance anticipates nothing, preferring instead a kind of present situation that is neverending. The game pieces are on a predetermined path, no space or time for a mysterious encounter with what might threaten the status quo. In other words, abundance as understood by those making large payments might be real, but it has nothing to which it might be directed. Even the good that might come from a large sum of money is itself limited because there is no vision with which it might be accompanied.

Not so for the widow. We know, plainly, that she is the “good example” in the sort of living parable playing out in front of us. Jesus says that she is giving out of her poverty, and while this straightforward reading has its merits, it has also been misused to manipulate many into glorifying poverty or, in the worst case, used to heighten the already violent imbalance of resources. Instead, I suggest we take seriously why Jesus might be giving the widow’s contribution as an alternative to the large sums given by the wealthy. It seems that this has less to do with the size of the gifts, even relative to the resources of the givers. That would be too easy a lesson on abundance. Rather, the widow’s gift represents a kind of abundance that is foreign to the order of the world. Such true abundance is, as expected, completely alternative to how the wealthy and powerful have been described. Its sincerity comes from its sacrifice, to be sure, but also from its capacity to exist beyond itself.

When pairing the actions of the widow with the words we read in Ruth and in the appointed psalm, we can hardly miss the tone of expectation. The widow’s gift, and Jesus’ recognition of it, is a clear sign of anticipation. The widow, of course, has no realistic expectation that her life will change materially. If she belongs to the faithful community, she should be taken care of by the instruction of the law. But there is no sense of self-preservation in her actions. She is embodying the kind of abundance that moves Naomi to seek wellness for her “daughter.” She is moving in the tradition of the psalmist, who lives in expectation of new life as a heritage from the Lord. Where the widow has only seen destruction and social stratification, she has responded with the kind of hope that only those who know true abundance. We don’t get to know exactly what compels this woman to give all she has to live on. I think it is safe to say, though, that we should not explain it away as some kind of reckless abandon. Her gift is notable to Jesus not because it may put her on the brink of disqualification in the economy of the day. In fact, we know from other stories that Jesus cares deeply about the welfare of those on the margins. It seems more likely that Jesus is lifting this up as an eschatological paradigm. She anticipates what is otherwise missed by those who can only thrive in the moment.

Friends, living in true abundance does not come naturally. We cannot and should not ignore the well being of our neighbors at the moment. But we would do well to broaden what it might mean to eschew the kind of abundance that draws its attention here and now and into true abundance that is only intelligible in the context of another kingdom, one in which our imaginations might be shaped beyond what seems to be.

Another way of looking at this story is that Jesus is calling attention to the coercive nature of the religious rulers, who intimidated and convinced the widow that she must give all she has left. In this reading, Jesus is not praising this kind of giving at all. Not that he calls us to keep all we have—of course we are called to be generous—but he cautions authorities about manipulating the poor.